As a designer, it helps to draw inspiration from other disciplines now and again. The world of modern and contemporary architecture, for example, has produced some truly jaw-dropping monuments to human ingenuity and aesthetic sensibility that are certainly worth a good look.

We’ve rounded up a selection of some of the most famous architecture of the past 150 years (with an emphasis on the contemporary) and organized them according to 10 design principles they demonstrate, which carry over to virtually all creative work. Here they are:

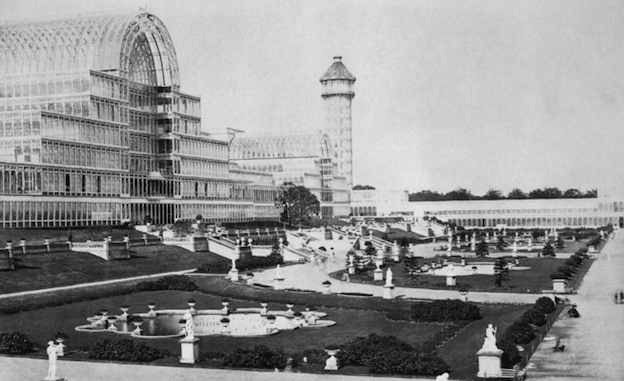

1. Test technology

The invention of steel in the mid 19th century allowed architecture, which was previously based in stone masonry, to soar to new heights. Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, constructed in 1854 entirely from steel and glass, triumphantly celebrated this new potential, and in 1889 the Eiffel Tower harnessed it to become the tallest structure in the world, at 324 meters.

It has of course now been outdone, most recently by Adrian Smith’s Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which rises a whopping 828 meters above the ground.

2. Bend the rules

Skyscrapers have traditionally been vertical — until architecture firm OMA, headed by Rem Koolhaas, got to work on China Central Television’s HQ in Beijing. Their groundbreaking structure is actually a loop consisting of 6 parts, 3 of which are horizontal. Why not?

3. Stick to your principles

Modernism is not known for producing the most cheerful of buildings, but rather ones of intellectual integrity. The Bauhaus school, which operated between 1919 and 1933 in Germany, espoused strict principles of minimalism and pure functionality, and its practitioners stuck to these no matter how much resistance they encountered.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in Manhattan, erected in 1958, is an exemplar of the so-called International Style. Just 20 blocks uptown, Marcel Breuer’s brutalist cube for the Whitney Museum of American Art has been proudly irritating its posh Madison Avenue neighbors for almost 50 years (though the museum will enter a new home with far more windows next year).

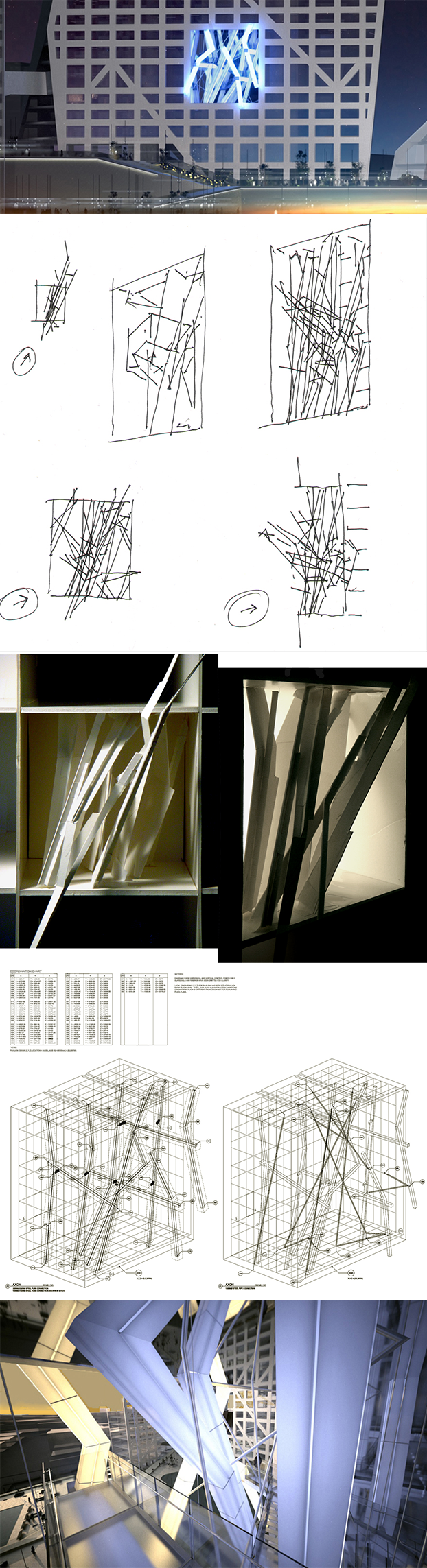

4. Sketch your concepts

There is a misconception that architecture is a purely rational art, based in math and engineering with just the slightest margin left for aesthetics to enter the equation. While this may sometimes be true, certain architects demonstrate otherwise, and the proof is in their sketch work.

Zaha Hadid, an Iraqi-British architect, puts special emphasis on form. Her buildings, like the MAXXI Museum in Rome, often start as abstract sketches (top left corner of the image set below) or even paintings (middle image in the set below).

Lebbeus Woods, meanwhile, was famous for constructing almost no buildings at all. A “theoretical architect,” his work consists mostly of amazing drawings, some of which would have been extremely impractical if not downright impossible to build in real life.

At the end of his career, however, he managed to bring one of his ideas into the physical world. Called Light Pavilion, it is an “experimental space” that marvelously interrupts a Chengdu office building.

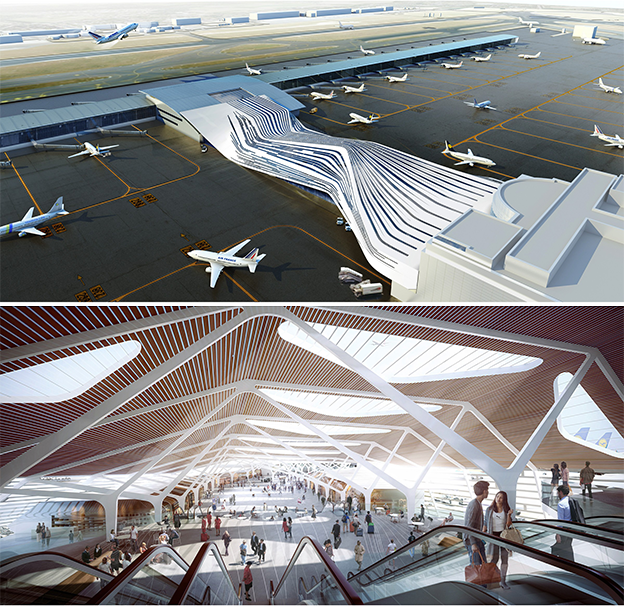

5. Solve problems

Great creatives often think of design in terms of problem solving. This is certainly true of the innovative Dutch firm UNStudio. In their work for Brussels Airport, they were tasked with creating a passageway that would a) seamlessly connect three disparate structures, b) accommodate passenger flows, operational as well as security processes, c) create new room for commercial spaces, and d) emblematize Brussels’ ambition to become a European transport hub. Their breathtaking design does all this and more.

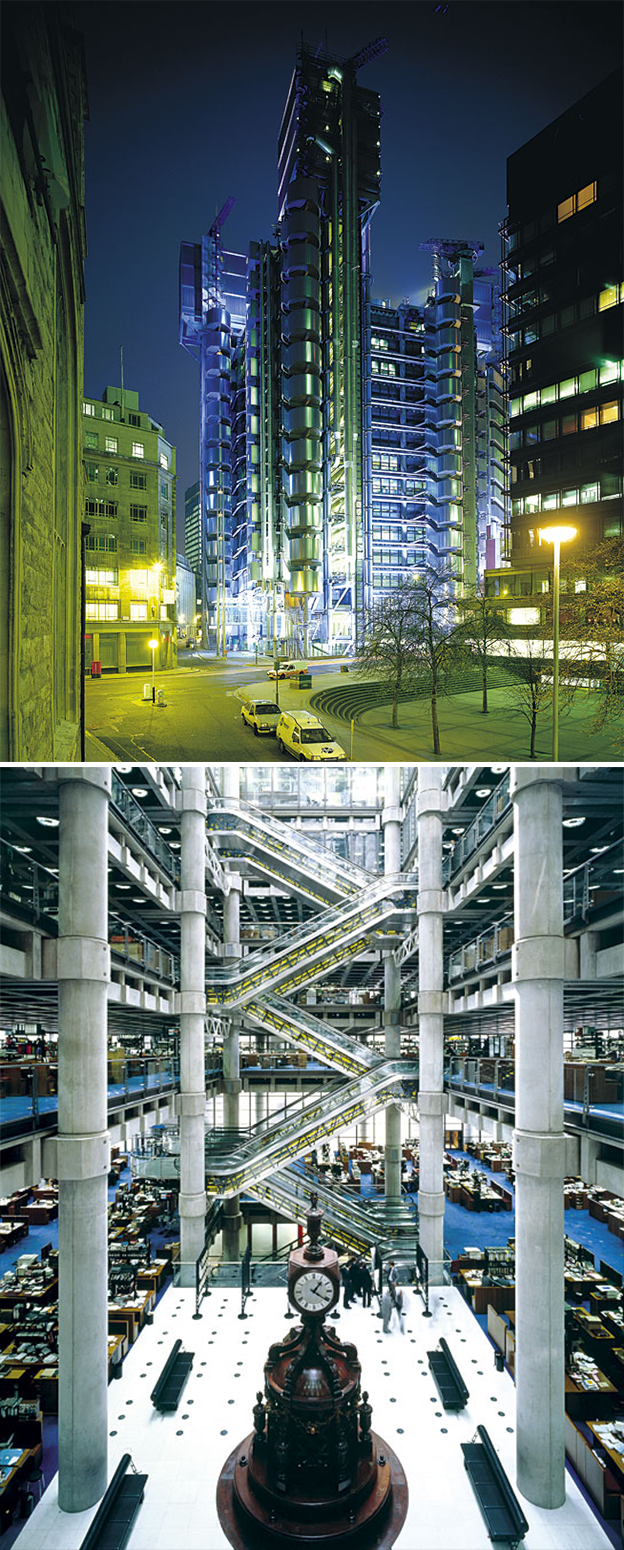

6. Get noticed

The word “iconic” gets bandied about a lot these days, but for many architectural achievements it seems truly apt. Especially in recent years, distinctive-looking buildings have become a way to identify an entire city or region.

The Sydney Opera House, for example, basically functions as the city’s de-facto logo. Jørn Utzon, a relatively unknown Danish architect, beat out dozens of celebrity architecture firms with his breezy design, which was submitted as part of an international competition.

Richard Rogers’ building for Lloyd’s of London, an insurance market founded in 1688, is one of the most curiously futuristic buildings the firm has ever done — divisive, but certainly memorable.

7. Switch gears

There’s no rule that says an artist must choose a style and stick with it. Some of the most inspiring creative thinkers make abrupt shifts, and no one represents such a course better than Frank Gehry.

While lately he has become known for flamboyant, almost painterly masterstrokes like the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, his earlier work was often quite different. Consider his Danziger Studio: while beloved by fellow architects, it is hardly eye-catching.

Indeed, it was actually designed not to stand out but to blend in to its slightly tacky Los Angeles neighborhood, and was purposely painted a drab grey with the expectation that L.A.’s smog would color it that way anyhow.

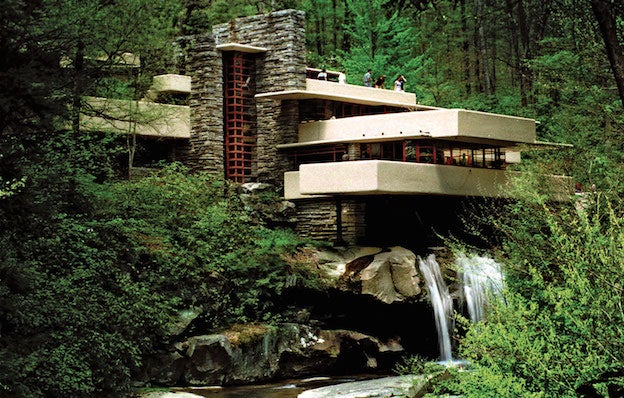

8. Mind your environment

This principle is pretty straightforward. Architecture always enters a preexisting environment, and in turn affects its environment through energy consumption, among other things. Some of the best architects of the past century have put these concerns in the foreground.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1935 masterpiece, Falling Water, is a rural home built into a hillside without disturbing its surroundings — including a waterfall that runs under it. Renzo Piano’s California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, meanwhile, is famed for its “living roof” — an actual garden that helps to reduce the building’s carbon footprint.

9. Repurpose

The last two sections of this blog post likewise have to do with transforming a context you have inherited or otherwise been given, rather than simply tearing down and starting fresh. New York City’s Highline park is an inspiring example of repurposing an existing structure.

As of just a few years ago, it was an abandoned rail line overgrown with weeds and shrubbery, slated for demolition (top image in the set below). But with the help of an architecture firm and a landscape architecture firm, it has been made over into an immensely popular above-ground park (bottom image in the set below).

An analogously awesome phenomenon is the re-purposing of industrial shipping containers into architectural units for homes or apartment buildings.

10. Combine new and old

Anyone who has done branding work is probably familiar with the task of creating something fresh that will still have continuity with, or may even need to coexist with, the system that came before. In architecture, this challenge can take on quite a literal dimension.

Hearst corporation wanted to build a skyscraper at its midtown Manhattan site, but did not want to lose the beautiful, historic façade of its former building. Architecture firm Foster + Partners promised to let them have it both ways: they gutted the old building while preserving the façade, and essentially just plopped a shiny new tower right into the middle of it.

The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam faced a similar challenge. It wanted to expand its contemporary collection into a new wing that would look sleek and modern, while still integrating with the existing building, which was created in the 19th century in an ornate 16th century style. The architecture firm’s solution has gotten mixed reactions, but one thing is sure: it was a bold move.